For India, A Crucial Moment In the Fight for True Democracy

March 13, 2021

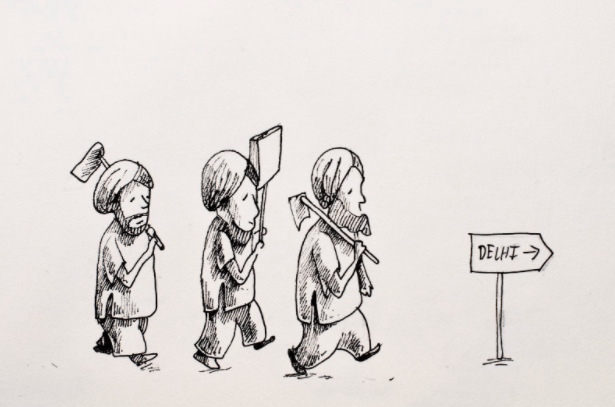

In what some call the “largest protest in human history,” hundreds of thousands of farmers, mainly from the northwestern states of Punjab and Haryana in India, marched towards the nation’s capital, Delhi, protesting what they believed were unjust bills passed by India’s Parliament in September 2020. The Indian government’s overwhelmingly negative response towards those who decried the bills as well as its refusal to meet many of the farmer’s demands has put forth questions as to the integrity of India’s democracy and its steps moving forward into the future, especially regarding its predominantly nationalist leading political force, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

For decades, the Indian government has offered a guaranteed price to farmers looking to sell their goods– the only way for farmers to disperse their produce was to sell through an auction at their state’s Agricultural Produce Market Committee. There were restrictions on who could make purchases, and every farmer was insured with at least the minimum price the government had to offer for their goods. Through these previous laws, farmers could form reliable guides and plan investments and decisions far in advance, ensuring financial stability. However, under the new bills by India’s houses of Parliament, the system will be dismantled, with farmers now having the freedom to sell their goods to whomever they wish at whatever price. Nevertheless, farmers argue that these laws will leave them vulnerable to corporations looking to drive down costs for produce, lower profits, and prevent farmers from earning their livelihoods. Junior Sanjana Paramesh notes, “Farmers are an integral part of India, feeding hundreds of millions of people, and that they need a higher government-set [minimum support price] to ensure that they can make a decent living instead of letting large corporations dictate the terms which could seriously hurt farmers.”

Outraged by the Indian government’s new bills, more than 100,000 farmers marched on Delhi, who were met by frequent police violence, with tear gas and water cannons being deployed against protesters. Protests continued through December, and farmers staged hunger strikes and marches despite the Indian government’s continued failure to reach an agreement with unions. However, in mid-January, the Indian Supreme Court suspended all three laws for 12 to 18 months while it continued negotiations. Paramesh adds, “An 18-month hold on the new policies is going to do nothing but delay the inevitable resurfacing of the current protests.”

The Indian government has been criticized internationally for its undemocratic efforts to suppress protesters and jail activists for speaking out against the state’s unjust acts. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing party, the BJP, have also been met with severe condemnation for the facilitation of police violence and refusal to meet farmers’ labor demands. With the 2020-2021 Indian farmers protests being the most considerable and most turbulent civil disturbance in the nation’s history, along with the government’s continuous suppression of democratic human rights, it is unclear whether negotiations will be adequately met within the 12 to 18-month time frame, if at all.