Colross–the quintessential PDS building, is a Georgian-style mansion located at the entrance of campus. Most know it as home to the Admissions, Advancement, and Alumni offices, or simply as the building they were interviewed in, but few, including members of the faculty, know the true history of the building.

A Plantation Home in Alexandria, Virginia

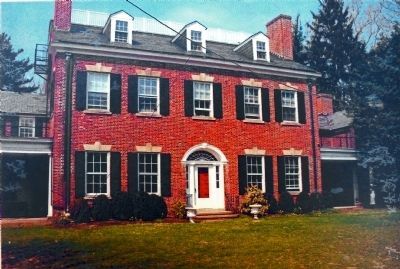

Colross as it stood in the early 20th century in Alexandria, Virginia (Photo/Allen C. Brown)

Built in roughly 1800, Colross—also known historically as Belle Air and Grasshopper Hall—was constructed in the Old Town neighborhood of Alexandria, Virginia by merchant John Potts as a forced-labor cash-crop plantation. The estate—occupying an entire block of Oronoco Street—housed gardens, orchards, and was—and still is to this day—well-known for its stunning architecture. Throughout the 1800s, the building had many owners, generally prominent white merchants. Furthermore, as it was a plantation, records indicate that many enslaved people worked on the plantation and in the mansion itself.

During the Civil War, the building was seized by the Union, and, according to local legend, two deserting soldiers were executed on the back steps of Colross (the side that faces the Carriage House now). Other stories have also described the building as being haunted.

Middle School Humanities Teacher Amy Beckford wrote her masters’ thesis on the building. When reflecting on the process of writing this thesis, Ms. Beckford stated, “I was doing it from a perspective of recording the building, which is something that happens in historical archaeology. I was trying to just capture its features and how [they] have changed over time.” She shared that in order for Colross to be a part of PDS, changes were made to transform it into an office space while “also trying to preserve its historic character.”

As the city of Alexandria industrialized around it, Colross transformed from a rural plantation to a home to house workers for the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation during World War 1. The owners divided up the rest of the property to build warehouses, leaving just the building standing. In 1927, however, a massive tornado struck the city and mansion in ruins.

“Brick by Brick” Colross is moved to Princeton

Colross building after being reconstructed in Princeton, New Jersey at Princeton Day School (Photo/Allen C. Brown)

In 1929, John Randall Munn, a Princeton native and wealthy industrialist, purchased the run-down building and dismantled it brick-by-brick. He hired people to disassemble the ruins, and ship the materials up to his land on the Great Road. For years, architects and construction workers from all over meticulously reconstructed the building trying to recapture every fine detail it once had. When Munn died in 1956, Geoffrey W. Rake purchased the estate. In 1958, Dean Mathey, honorary chairman of the Bank of New York and former tennis star, and his wife donated the land surrounding Colross for the campus of the newly established Princeton Day School. With that, PDS decided to purchase Colross, which the land bordered on three sides, from the now-widowed Mrs. Rake to fill out the campus.

Modern-Day Architectural Report Cites Evidence of Outbuildings

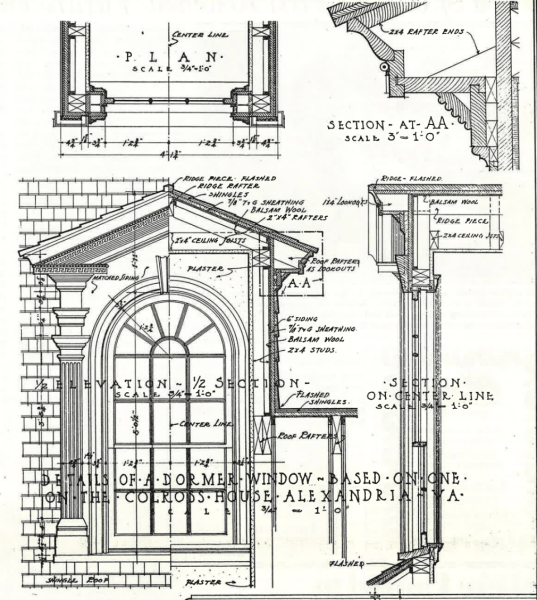

Colross architectural report from Alexandria, Virginia (Photo/Princeton Collector)

In 2004, Diamond Properties LLC, looking to build a luxury condo unit on the Alexandria location of Colross, paid a private firm $100,000 to explore the land Colross once stood on for any architectural remains. Construction since the building’s removal had already destroyed most remains. However, archaeologists found ceramic and glass remains dating from the early nineteenth through early twentieth centuries, along with many burial sites. Among the findings, archeologists also discovered the remains of buildings that housed enslaved people, solidifying evidence of the presence of slavery at Colross.

Enslaved People at Colross

Colross was a plantation located in the South during the 1800s, a time and location when slavery was legal. Records compiled in the 2004 archaeological report indicate that dozens of enslaved people worked on the Colross property throughout its history in Virginia, contributing to the wealth of the white owners who lived in the home. Ms. Beckford encountered much of this history through her research. She stated, “because it was in Alexandria, we know it had the location of being in a slave state, we know it had owners whose property is described as including enslaved people, and we know that it had a certain workshop quality in terms of some of the activities that we’re going on there and that involved the enslaved people who lived at Colross at the time.” She also added that the architectural report failed to expand upon the details of the enslavement that occurred at Colross. “I was appalled. There is almost no mention, relative to the 200-page report, of the enslaved people. They’re very glossed over, mentioned in passing at best, with the kind of language that dances around the issue.”

PDS’s Past Response

This news may come as a surprise to many, as few members of the PDS community know that Colross was moved from Alexandria, let alone that enslaved people worked on the estate. There is nowhere in the curriculum where this is taught, nor a mention on the website or in the building Colross itself. However, for many Black members of the community, the history of enslavement was apparent immediately upon walking through the halls of Colross.

Director of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Anthony McKinley stated, “if you knew about that era, and where Colross originated from, it doesn’t take much to put two and two together. I know as an African American person, that if I knew about that, that would be the first thing I’d jump to. But I know that is something very specific to me and my identifiers.” He added, “I’ve never been able to walk into that building without thinking about that.” Assistant Director of Admissions Teddy Brown ‘08 stated that though it was known by some, “The history of Colross is not something that I have experienced people discuss openly at this school. I think we have done a lot of good in really reevaluating the feeling we want to give families when they walk through this building, but a lot of that also needs to be recognizing the innate feeling this building might bring up for certain people. Actively counteracting this by talking about and leaning into the discomfort of the history; these are things that could be done.”

Up until now, little has been done. Former Head of School Paul Stellato shared when learning of Colross’s history: “In the late summer, early fall of 2020, an Alum reached out to me to tell me that she had found a study from the city of Alexandria, Virginia, which had discovered or suggested, that one of the families that owned Colross had kept enslaved people on their property. She then brought it to my attention, and we had a terrific conversation. I don’t know that I did anything with that information immediately.” Mr. Stellato added, “I don’t remember how much later, I asked Mr. McKinley, Ms. Lee, Ms. Beckford, Mr. Bobbitt, to talk a little bit about how we might go about exploring this. We had a couple of meetings and that’s about as far as we had got. We had not determined what the next step would be. Because at this point, the question was ‘does this go immediately to the Board of Trustees for a conversation?’” Mr. Stellato also mentioned, “We had explored the Slavery Project at Princeton, a similar project at Brown University, the way in which students were involved along with their board and faculty, but in both cases there were enslaved peoples on the campus in the building—we were a step removed from that. And then we began to think about what the time and resources would be involved and the amount of research that we would need to do.”

The project never developed further, “we got part of the way down the road, we began to educate ourselves … but we hadn’t made a decision about what we were going to do. … Colross, in many ways, is the core of our school experience and there is something very rich here and making sure we take the time we need to agree on an outcome that we want to see. How we can honor those that were enslaved in Colross but never stepped foot on our campus is very important. … I would have loved to make more progress on this than I did.”

Future Direction

In July of 2023, Kelley Nicholson-Flynn took over the helm as Head of School. Dr. Nicholson-Flynn eagerly accepted my request for an interview and I spoke with her on August 24th, before the school year had begun. She shared, “I’ve had two strings of information come through, one was Mr. Stellato left me a magazine that was written about Colross … it doesn’t grapple with the history of the building. Head of the Board of Trustees Christopher Bobbitt sent me a longer document that came from the archeological dig. What I’m interested in thinking about is what’s the right path forward.” She continued, “what I would want is for students, in concert with adults, to explore how we could appropriately recognize the complicated history and make a choice about how we should mark it. I would want it to be a collective conversation.” She added, “Doing something like this right means listening to voices that aren’t necessarily going to agree with each other.” She shared her next steps, “I would like to put together a group that wants to work on thinking this through, who is going to be committed to it … and then make a recommendation of how to proceed.”

Over the next month, Dr. Nicholson-Flynn spent time investigating the history of Colross and considering PDS’s response. She stated, “I see a couple of potential paths forward… there’s a question of scale or scope. You can do these big public history projects, those are powerful and can be more challenging and can be costly, that’s one option that I’d like to explore. The other is more locally focused to the PDS community and the folks that are here on campus, which is to say that there is really no doubt about the history of the building, and given this, what is the appropriate way for our community to acknowledge it? … I imagine that we would have a working group that would do this research and make a recommendation to me or to the Board. It feels like the more locally focused seems more realistic to do in the short run.”

It appears that Dr. Nicholson-Flynn is passionate about this project and is actively trying to grapple with this history. There are many opinions on what should be done with Colross, even among faculty. Some faculty I spoke to believe that a plaque recognizing the history of enslavement would suffice, whereas others believe that PDS should move away from the building and move the offices housed inside of it. Although those I spoke to did not always agree on a path forward, they all shared a similar hope: this has the potential to be a moment of unity for the PDS community. We have a complex piece of history on our campus that symbolizes something horrific, and finding a way to grapple with it that honors the lives of those who were enslaved in the building is imperative.

Colross as it stands today (Photo/Wikipedia)

If anyone would like to offer their opinion after reading this article please email me at [email protected]. Finally, if anyone is interested in contributing to a potential project please email Ms. Matlack at [email protected].