Holocaust survivor shares her story

April 11, 2016

In the course of our lives, we interact with millions of different people. Many of these strangers pass by us unnoticed, but occasionally someone stands out. Maybe it was a random person on the street who smiled at you, or someone who held the door for you. Or maybe you owe a stranger for getting you a particular job offer, introducing you to a future friend or love, or even saving your life. For many Holocaust survivors like Ruth Ravina, kind, brave strangers were the difference between life and death.

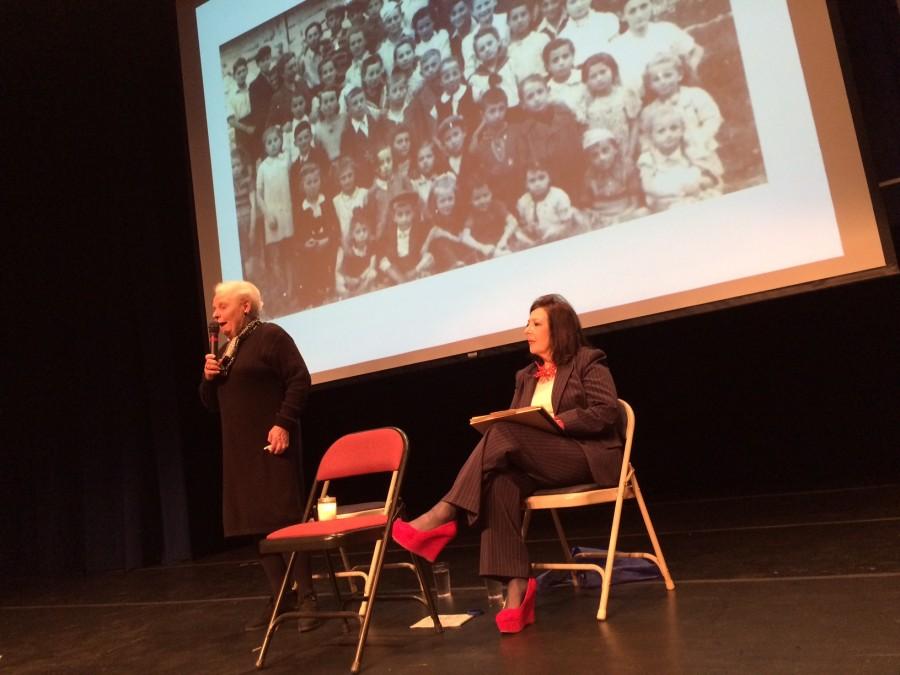

Ravina is one of only 195,000 Holocaust survivors alive today, as senior Noam Yakoby noted when introducing her during her recent visit to PDS. Due to the survivors’ old age, we will be the last generation to be able to directly hear their stories, Jakoby reminded us. It is important to hear these speakers in order to remember the genocide that happened, as well as the significance of promoting tolerance so that the world may never experience anything even close to the Holocaust ever again. Ravina’s speech began with a few moments of silence as a candle was lit in memory of the six million Jews, as well as other racial, religious, ethnic, social, and political groups, who were murdered in the Holocaust.

Ravina’s story started in 1942, when she was about five years old and the Nazis invaded her hometown in Poland, separating Jews into a ghetto. The last time she saw her father and uncle were when they were being taken away from the ghetto with the other men to provide slave labor for the Germans. Ravina remembers always being called a “filthy Jew” and having Nazis loot her house for everything of value, including the furniture. One day, some neighboring girls in the ghetto were talking with a German soldier and discovered that all the Jews were about to be taken to Treblinka, which is now infamous for having been an extermination camp, with the second highest death rate after Auschwitz. These neighbors took Ravina away from her family and hid her in the farmhouse of a Christian family who knew her. When Nazis searched the house, Ravina successfully hid in an oven, but the dangers of harboring a Jew were too much for the family. One of the boys in the family managed to bribe guards in order to sneak Ravina into the same concentration camp as her mother.

She continued to remain hidden in this camp for several months, and was then moved to a second camp, traveling in her mother’s knapsack to avoid being seen. Ravina stayed at this camp for one year, but during this time she was discovered by the guards. She was taken to the commandant, thinking that she would be killed, but he found her amusing and spared her life. After that, she was ordered to come into his quarters every night, where he would throw food at her and his dog and have them catch it in their mouths, dehumanizing her for his own enjoyment.

Another time, Ravina was put onto a truck with many other Jewish kids who had been hiding in the camp, and they were all driven to a giant hole being dug in the ground, which was most likely to be their grave. But as young as she was, Ravina was extremely brave. She jumped out of the truck while it was waiting, and found a woman on the road. This woman, who turned out to be a nurse, hid Ravina under her cape and took her back to the camp infirmary. After her mother found her there, Ravina once again stayed hidden, with the commandment and guards thinking she was dead.

In January of 1945, Ravina, her mother, and her cousin were liberated by escaping as the Russians were fighting their way toward the camp. When they returned to their hometown in Poland, they expected to find other family members. Instead they discovered that they were the only ones who had survived. Recovering from the Holocaust was another struggle in itself. There were funerals to attend, and too many people to mourn for. Ravina later found out that her father was killed less than a week before the end of the war. Her mother was so poor that Ravina had to spend the next six months in an orphanage in order to get food and shelter. She later came to the United States, got married, and had two children and many grandchildren.

Survivors like Ravina are inspirations in many ways. Despite the tragedies she went through, she did not express any hatred or lack of hope in humanity, and she was very comfortable sharing her experiences–both the horrors and the miracles. Ravina clearly remembers all of the people who saved her life: the German soldier who gave the warning, the neighboring girls who took her to the safe house, the Christian family who hid her, the one boy in that family who reunited her with her mother, the nurse who brought her back to camp, her own mother who saved her countless times, and even the commandant who decided to keep her alive. Ravina was–and still is–incredibly brave and resilient. The moderator who came with Ravina used this experience to encourage us, even as students, to ensure that something like the Holocaust never happens again. She described that while natural disasters are unavoidable killers, wars can be prevented, and so we must be careful with words, observe others’ words, and vote for good leaders. There are times when we must decide to either be a bystander or take action, and Ravina’s story demonstrates the huge impact that a small decision in a single moment can make on someone else’s life.