PDS Celebrates African American History

April 30, 2020

To this day, wealth in America is unfairly distributed between people of color and white people, unfair housing practices impact millions, and America is by no means a safe-haven for many disadvantaged communities. And yet, so many have been able to persevere. Each year, PDS takes the time to celebrate African American History and those who have accomplished so much in the face of discrimination, disenfranchisement, and segregation. Though such recognition ultimately culminates in a Black History Month celebration at the end of February, the acknowledgement starts even earlier, on Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Thoughts on Erin Corbett?

For the Day School’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. assembly this Friday January 17, educator and activist Dr. Erin Corbett was brought in to speak to the Upper School. Her talk was evocative and emotional, leaving some deeply moved and inspired, while others felt dismayed at the message she had conveyed.

Corbett works in a variety of roles, from expanding educational opportunities for many populations and specifically for those incarcerated, to researching federal policy relating to education and the effects of the justice system. Corbett holds a B.A. in Psychology and Education from Swarthmore College and has earned an MBA and a Doctorate of Education from Post University and the University of Pennsylvania respectively.

Talk of Corbett rumbled through the PDS atmosphere after her speech, with some arguing that her use of the word “manipulate,” in regards to her treatment of those who disagreed with her rhetoric, suggested she would just push the white moderate out of her way when attempting to take action. This message would, as such, go against King’s belief that everyone should come together to take direct action. Certain members of the PDS community felt the speech was specifically targeting white people, without including them into the movement.

On the other hand, though, some interpreted what she said as an emphasis on the importance of seeing the humanity of those you work with and making connections with those that might disagree with you, in order to obtain their support and make real progress. Corbett spoke of “co-conspirators” or white allies who could help with activism, which implies a wish for an alliance with different demographics in order to achieve change. It’s true, there was a strategic element to her speech, but King himself in his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” spoke of scheduling demonstrations for the Easter season because that is “the main shopping period of the year,” rendering her rhetoric relatively similar to his.

Corbett ultimately did seem to have a positive effect on the PDS community. As senior Julia Chang put it, “Corbett’s perspective was what has been lacking in lot of speeches given at PDS. She didn’t water anything down for the audience and gave the facts as they were. I really appreciated that.”

A transcript of the speech can be viewed below, and an audio clip is attached.

ERIN CORBETT ON REV. DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

It’s fair to say that there are two things that I know very well: I know education, and I know justice. I spend my day holding legislatives accountable—including calling them out on Twitter and in person—and planning direct action in their offices, rallies, and capitals, and generally making a lot of noise being a political agitator. And I love it.

But I’m not here to focus on all the things I love to do; I’m here to talk about why it is so important that we understand the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, that we remember him and praise him for more than his “I Have a Dream” speech, more than his refrain of “free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty we’re free at last.”

It is critical that we move beyond what has become the tritest, most unsophisticated, most egregiously oversimplified and one dimensional analysis of King’s actual impact on movement building, community organizing, and grass roots and grass tops political advocacy that the Western world ever deigned to accept. For many others have done much more work, but their methods and strategies were not as politically palatable as King’s—and he knew that.

Movement building or revolution making is a process. It is not a fleeting hashtag on a sign with names that change because we cannot seem to figure out how not to shoot unarmed people. It is not falling into trendy justice-adjacent actions based upon individual contributions, all while ignoring the people on the ground, in communities, doing the hard work. (I like to call this the Kardashian Effect). It is not voyeuristic volunteerism, taking photos with black and brown children during spring break so you can feel good about yourself.

It is about discipline. It is about focus, and a willingness to risk it all to make this world better.

How are y’all feeling so far? Did I hurt anyone’s feelings? Sorry not sorry.

King was one of many who figured out a formula to do what he could to improve the lives that we all lead, and there are lessons we should internalize in order to keep his dream from further devolving into a nightmare.

King, in his Letter From a Birmingham Jail in 1963, wrote about the four critical tenants of nonviolent campaigns against injustice. This letter, and his clear explanation of when and how we should become involved as brothers and sisters of the human race, resonate even today more than 56 years later.

Written two months after the assassination of Malcom X and on the eve of heightened visibility for the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, King’s words encouraged all who fight for justice and against injustice to not only examine the world but themselves, in order to determine the extent to which they are really about that revolutionary life.

Because revolution requires organizing; it requires the strength to understand that you can lose absolutely everything. Your reputation. Your job. Your home. Your family. Your life. And it consistently demands exorbitant sacrifices. Because revolution isn’t about the revolutionary or the justice warrior; it is about how we are able to leave the world better than we found it.

So in his Letter From a Birmingham Jail, King gives us some advice on how to make sure we are properly fighting injustice. He tells us that first we must do our due diligence around data collection. If you don’t know what you’re talking about and you sound a little bit off, people aren’t going to listen to what you have to say. They are not going to take you seriously, and that can undermine your cause. So, as you are here at a school like Princeton Day School, that focuses on things like critical thinking, analytical thinking, and objective data collection and analysis, you need to understand how that is preparing those among you who may start to do this revolutionary work, this justice work.

I’m going to present a few pieces of data now that outline justice and the status of justice in the United States, and I will use two of King’s primary focuses: racial equity and income-class inequality.

Here’s one piece of data: 933 people were shot and killed by police in 2019. That’s almost three people a day across the country, shot and killed by those who are supposed to protect and serve. In the police shootings we hear about, there’s this ridiculous process of determining the fault of the victim, assigning value to their lives, based upon how they respond to law enforcement interaction.

We hear, “they should have just complied” or “they shouldn’t have resisted” or “they should have told the officer they had a weapon.” Except, what we see with Philando Castile, he did exactly that, and was still shot dead. All of these excuses serve only to assign culpability for a misuse of force to the person who was not responsible. But the cops have been killing people for decades; from the Black Codes to the Jim Crow laws of the Reconstruction era, law enforcement has disproportionately policed, arrested, incarcerated, and killed black and brown bodies with reckless abandon. While we no longer have signs that say “colored only” in public places, we do have police officers in Texas shooting unarmed women in their homes on non-emergency safety checks.

Almost 30 years ago, Rodney King’s case brought police brutality to our television screens, in our homes, as the world watched. Not a decade later, Amadou Diallo was shot at 41 times and was hit 19 outside of his apartment in New York, while he reached for the identification the police had asked him for. Recently, a man was gunned down by police, while sitting in a parking lot, with his hands up, as he begged for help, sitting next to his special-needs client.

We are at a point where trust between the community and law enforcement has eroded so egregiously that it is hard to contemplate a time when this has not been the case.

The richest 0.1% of our population in 2017 took home 188 times more income than those in the bottom 90%. When we disaggregate those numbers by race and ethnicity, we see with even more clarity how practices like red-lining have left us with subsidies that are even more segregated than they were when segregation was a trendy word.

Places like Buffalo New York, Montgomery Alabama, Atlanta Georgia, New Orleans, Birmingham are still some of the most segregated cities in the United States, joining the ranks of cities like Detroit, Chicago, and Memphis.

Segregation happens when income inequality becomes residentially statute. Segregation is what happens when terms like “white flight” are used to describe the departure of white folks from certain neighborhoods, often accompanied by the pejorative “well there goes the neighborhood.”

But segregation also happens when we have to talk about terms like gentrification. In Washington D.C. Howard University is one of the district’s oldest universities and is an HBC, that is historically black college or university. Howard’s campus is nestled quaintly near 8th Street, in a historically black neighborhood with the PCS store that has played Go-Go music since 1995.

They’ve been playing Go-Go music loudly in the same store for the past 20 years. Recently developers have swooped into the neighborhood, bought up all the land, Built expensive high-rises and ways of gentrifiers have settled in. Recently, Howard was embroiled in scandal. People were walking their dogs and letting them use the bathroom on the main quad, a hallow place filled with tradition and memories for many of the schools famous alumni and obviously their current students.

Howard students rightfully encourage dog walkers to walk their dogs elsewhere—or at the very least be a responsible pet owner and pick up after their dogs (but mainly, they just wanted folks to walk the dogs elsewhere). One of the men who proudly walked his dog on the quad, who had lived in the neighborhood for less than 2 years (less time certainly than the school had been established), said to news reporters, “Maybe the campus should move.”

Incongruent culture clashes have been occurring in many formerly all-black neighborhoods all-brown neighborhoods, Especially in places like Harlem. When income and the access it grants allow people to lay claim to space that already has its own cadence, its own rhythm, its own pace, the inequities become more pronounced and create larger and more intense conflict.

So, how do we resolve these conflicts? King gives us answers. How do we make policy practice and accountability changes? Many have tried incremental change. If we look at current events, we see evidence in the First Step Act, passed in 2019.

So what we have in the First Step Act is an attempt by supporters to change some of the harms and to roll back some of the trash policies that came out of the mid-90s, such as the Violent Crime Act of 1994, who was written by then-Senator Joe Biden and was then signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

What the First Step Act did not do, however and unfortunately, is provide any sort of relief for people who were incarcerated in state prisons. What the First Step Act did was apply all kinds of retroactive credits program availability for folks in federal facilities, and additionally included approximately seven pages of convictions that were not allowed to participate in the program availability and be eligible for those good-time credits.

So, with a piecemeal part of legislation that, in many ways, split the justice community in half, you have one side that was in favor of anyone being able to get out of prison and the other side battling the desire to want people out of prison while wanting the government to do more.

The First Step Act had many supporters but also strong opposition, most vocally in the criminal reform space. Those in opposition rightfully noted that the Act called for piecemeal change that only potentially impacted a small number of the incarcerated population, when more progressive legislation could have provided state-held incentives to decrease their prison populations. These kinds of negotiations, however, are common when doing justice and equity work. Arguably, they’re common with any policy work, but they are especially common in justice and equity work.

We often find ourselves in the position where we have to ask ourselves, whose lives will we sacrifice to get some relief for some people? Who, when we think about it, do we value more than someone else?

These are questions that don’t always have the easiest of answers. These are questions advocate to ask themselves all the time. These are the questions that politicians ask themselves all too infrequently.

I had a meeting with a legislator the other day, who is actually my representative in the town that I live in, and I asked him point-blank why he voted for legislation that would disproportionately impact his community. And his response was, “There were just too many laws that we vote on. I can’t read them all.”

This is a legislator, talking to a constituent, who also happens to have a doctorate from an Ivy League institution, and who really enjoys her Twitter figures. What we have is a situation where legislators no longer feel accountable to the people that they serve, to the people who voted for them, and that’s why we end up in these positions where we need to make these piecemeal negotiations in order to get to a better place in equity and justice.

The next step that King talked to us about is this idea of self purification. So, I want to ask you all, what would you do if someone punched you in your face?

Collective Response from Audience: “Punch them back.”

None of you could be in King’s brigade. A lot of times, when we hear about King’s non-violence, we think that it’s non-confrontational. We think that it’s calm, that it’s just kind of walk-around-and-do-nothing, and let people just spit on you and slap you and turn hoses on you. It takes a lot to sit there as someone is hitting you, spitting on you, kicking you, sticking dogs on you. it takes a lot to do nothing. Because what happens when you punch that person back? Then there’s a fight. And if you are in the Civil Rights era, and you’re a black person, sitting at a Woolworth’s counter and a white person spits on you and you get in a fight, who is going to jail? And how then is your case advanced?

So, when you think about this idea of non-violence and you think about this idea of purifying yourself, in so much as you are prepared to literally risk it all, to risk life and limb to make sure that future generations have a good life, you have to understand that the sacrifices demanded of you will be exceptional.

Finally, King talks to us about Direct Action (literally my favorite). Protests, sit-ins, rallies, occupying officials offices, marches: these are the direct actions that follow careful considerations of each of the steps mentioned previously. These are the potentially costly actions. Twitter figures are easy to hide behind, but you cannot hide when someone filled with the rhetoric of vitriolic hate is intentionally split spitting in your face, pushing you, hitting you. You cannot hide as you hold a legislator accountable for voting in favor of legislation that made decimate families and communities, Separating children from their families. You must not hide, because you must understand that your fight today is someone’s fight tomorrow.

James Baldwin said it best in his “A Talk to Teachers.” He said, and I quote, “One of the paradoxes of education was that precisely at the point when you begin to develop a conscience, you must find yourself at war with your society. It is your responsibility to change society, if you think of yourself as an educative person. And on the basis of this evidence, the moral and political evidence, one is compelled to say that this is a backward society.”

King’s message of revolution, while cloaked more than adequately in non-violence, is not message that advocates for calm resistance, a resistance that one can pick up and put down depending on latest trend. It advocates for deliberate and intentional disruption of inequity through the process oriented approach that centers community voices, movement-building, and the education to know what you need to fight for, at which time, and in what venue. It advocates for calling out injustice when and where you see it, with calculated regard for potential outcomes.

Fundamentally, it calls for action, not bystander observation, and demands that—in order for us to make meaningful and transformative change—we must honestly reckon with the dreams we’ve inherited and the reality through which we must purposely and diligently try.

Thank you.

Question and Answer period can be heard in the attached audio clip.

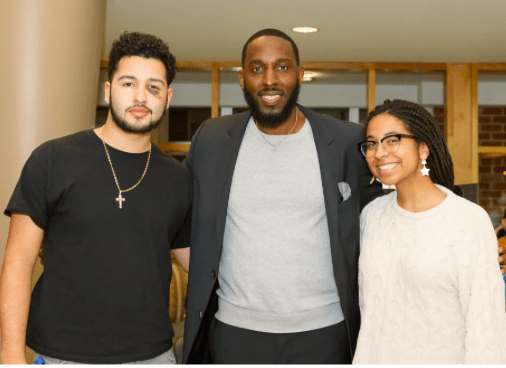

BLSU Co-Heads Senior Zoe River and Junior Josh Colon alongside Mr. McKinley. (Photo/Nazareth Mehreteab ’21)

Celebrating Black History Month at PDS

February 24th marked the annual PDS Black History Month Celebration. After opening remarks from Chair of Community and Multicultural Development Team Anthony McKinley, the audience heard from a wide range of PDS student speakers. Through his position in the CMDT, McKinley noted that he is “fortunate to be able to collaborate with such dedicated and talented individuals.” At the start of the event, 8th grade students Mikayla Blakes, Kingsley Hughes, and Lea-Jade Richards presented a video highlighting a series of interviews with members of the PDS community. The three had asked, “what would you march for or against?” and received a variety of responses, ranging from climate change to gender equality to racism.

After the 8th grade presentation, members of the Upper School shared original poems, essays, and personal narratives. To start off, senior Ahzaria Silas presented her original poem, “ Where the Blackness Runs.” Silas’s poem expressed the many societal issues black-Americans face today, such as racism and discrimination. Following this, senior Adayliah Ley shared her personal narrative, “Aisle Five.” This piece was a short story about Ley going to the grocery store and being approached by a woman who asked if Ley’s mother was her nanny. Ley explained that her mother and she look completely different, and shared her struggles of being mixed race.

French Teacher Monsieur Afemeku Playing Drums With Lowerschoolers (Photo/Nazareth Mehreteab ’21)

Seniors Fechi Inyama and Aidan Njanja Fassu shared “Dear White America” and an Interlude from “Mortal Man” respectively. Sophomore Andre Williams recited his original poem, “God Bless America.” All three of these pieces underscored the notions of racial inequity and injustice.

After the student-led portion of the event, Upper School English teacher Caroline Lee shared her original essay entitled “Why Black History Matters to an Asian-American Woman.” In her piece, Lee described the strong friendships her family members formed with black-Americans. She also explained that African-Americans and Asian-Americans both face the struggles that come with being a person of color in America.

The event ended with a beautiful drum circle led by Upper School French teacher Edem Afemeku and adorable lower schoolers. McKinley notes that “it’s fulfilling to see children, students, and family members of all ages partaking in this African tradition.”